|

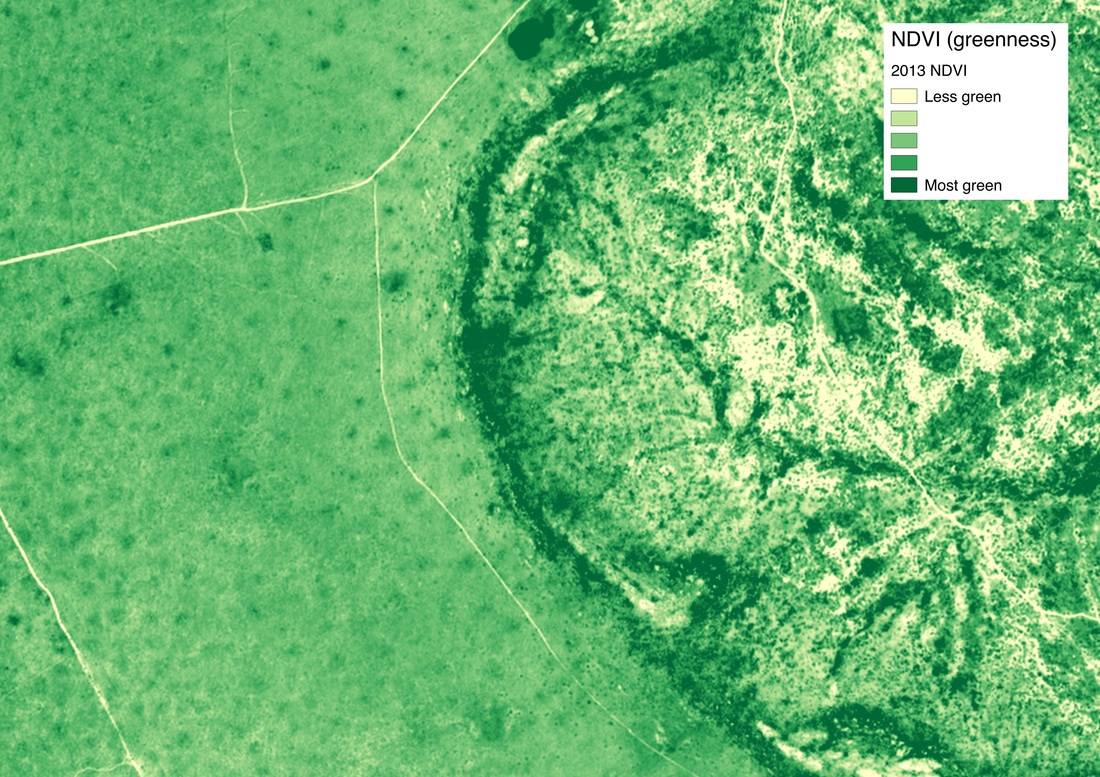

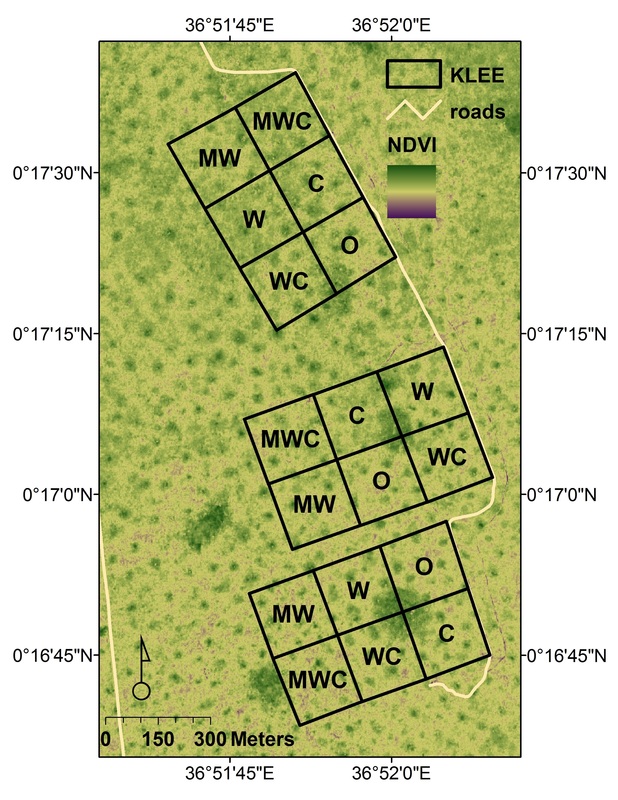

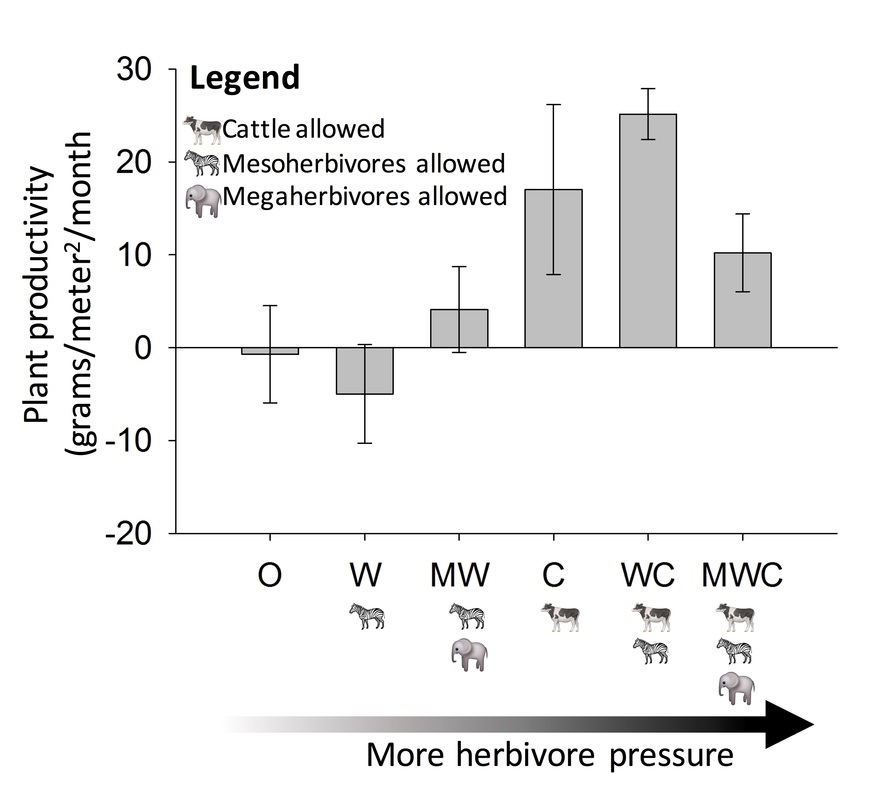

Author's note: This is a summary of our recently-accepted paper in Ecological Applications. Check out the original here or here. What animals come to mind when you think about savannas? Elephants? Gazelles? Giraffes? How about cattle? In addition to being home to a diverse array of wildlife, Mpala Research Centre (where I conduct the majority of my PhD research) also manages a number domestic herbivore species such as cattle. This arrangement mirrors rangelands worldwide, where wildlife and livestock often graze side-by-side. However, there is surprisingly little research that explores how different herbivore communities influence and alter ecosystems. Does a savanna with only cattle look the same as a savanna with only wildlife? What about a savanna where cattle and wildlife graze together? Understanding the role of herbivore identity is becoming increasingly relevant in a world where wildlife species are being partially or completely replaced with domestic species such as cattle. Since 1994, the Kenya Long-term Exclosure Experiment (KLEE) has experimentally manipulated the presence of three different groups of herbivores – mesoherbivores, megaherbivores, and cattle – to better understand the consequences of changing herbivore communities. I am conducting research within these plots that explores how different herbivores influence critical ecosystem functions and services. One recent project I have been working on asks how different herbivores affect plant productivity. It’s a simple, but surprisingly unexplored question. You might expect that because herbivores eat plants, they would reduce plant production. In fact, it’s difficult to predict even the most fundamental effects of herbivores on productivity. Some studies from similar savanna ecosystems have reported that herbivores boost productivity, while others have reported the opposite. To add to this puzzle, even herbivores with largely similar diets could affect productivity in different ways because of differences in how or when they eat plants. My colleagues and I collected data within KLEE to measure the effects of different herbivores on productivity. We measured plant productivity in two ways. First, we used productivity cages quantify how much plants grew over a given time period. We repeated our measurements multiple times over a period of two years to capture plant productivity in both rainy and dry seasons. Second, we used a series of satellite images to quantify the ‘greenness’ of the experimental plots in three separate years.  Two ways to measure productivity. Above, a productivity cage we use to measure how much plants grow in a given time period. Below, plants from space: a map I generated from satellite imagery to calculate the relative greenness of different plots in our experiment. Can you spot the roads? They are yellow. One big surprise of our measurements? Plants grew fastest in plots with cattle. We think this is related to grazing pressure; plots with the highest levels of grazing pressure also tended to have to highest rates of plant productivity. Many of the plants in this ecosystem have evolved under intense grazing pressure and are perhaps well-equipped to compensate for defoliation. In contrast, we found plots where all herbivores had been excluded had plant production rates close to zero. This could be the result of plant self-shading, a process where dead uneaten plant matter shades out new plant growth. Our study highlights the fact that replacing wildlife with cattle may have unintended consequences for how ecosystems look and function. Understanding the influence of different herbivore species will hopefully help us better protect and conserve ecosystems. Stay tuned as we continue to study the impacts of livestock and wildlife, separately and together, on savanna ecosystems.

4 Comments

For all previous blog posts, check out kenyeaah.tumblr.com

|

AuthorI am an ecology graduate student at UC Davis. I work in Kenyan savannas. Other interests: bikes, roller derby, jewelery making, and maps ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed